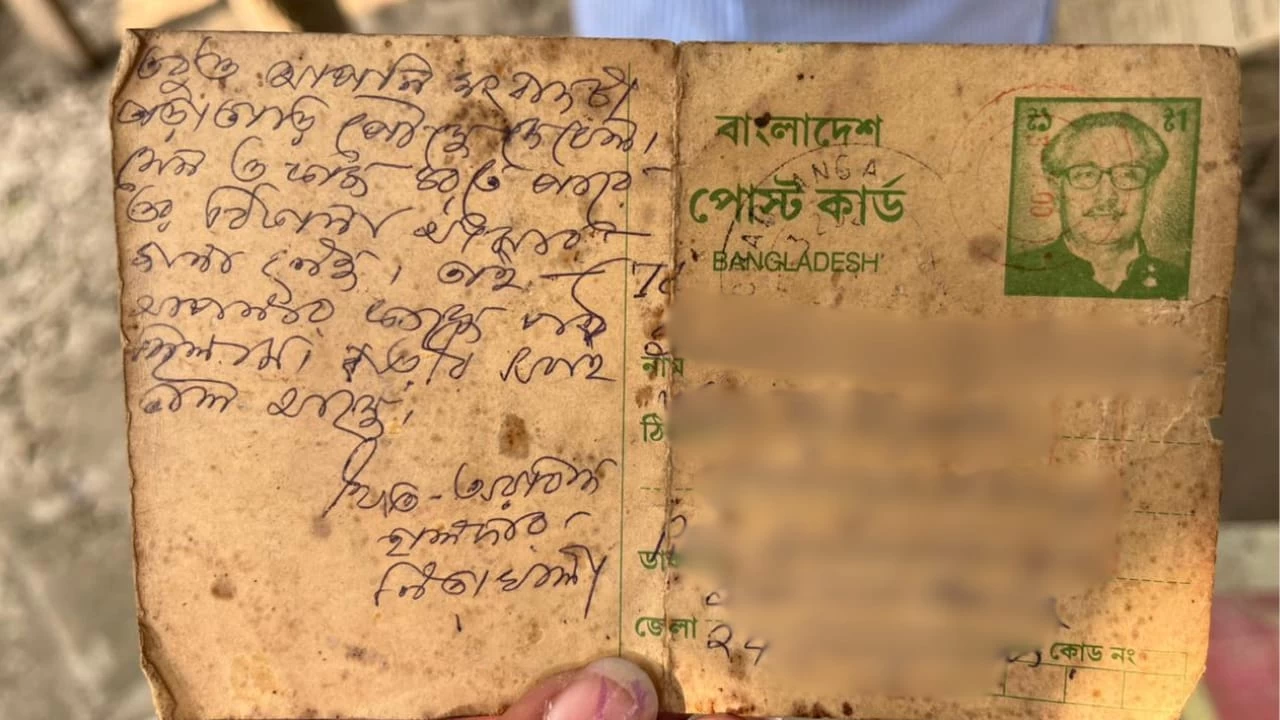

“I have my father’s letter”, 66 year old Thakur Mahanta got restless and rushed inside his humble house at Uttar Simulpara in North 24 Paragana’s Bongaon and came back with a small box. He had carefully kept a post card inside it, the last and only hand written letter from his late father post their separation. Mahanto is one of the many marginalised Hindus who had come to India during the 1970 turmoil in Bangladesh, leaving behind their families and a land they had till then called their home. Mahanta’s eyes turned moist talking about his father and the trying times he had witnessed before escaping death in Bangladesh. The post card had the picture of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, popularly known as Bangobandhu, the father of Bangladesh, right above the address column. The letter dated in early 2000 was addresses to Mahanto’s uncle in North 24 Paragana (India) where a father had enquired about his son. That is his only proof to claim his connection with the land where he was born. Mahanta is one of the many people who had demanded citizenship through citizenship amendment act (CAA) but now like others, he too is equally in despair after the CAA rules were commissioned on 11th March 2024, four years after the CAA bill was passed in December 2019 and right ahead of 2024 Lok Sabha election dates were announced.

The CAA rules make it mandatory for the applicant seeking citizenship to have some proof of identity issued by either the government of Bangladesh or Pakistan or Afghanistan, something tangible to show their link with the land they have left behind. “Evidence of the date of birth of the parents viz. a copy of the passport or birth certificate. In case of non-availability of passport of mother/ father, birth certificate of the applicant clearly indicating the name, address and nationality of mother/ father”, is one of the many asks, mandatory for every applicant to obliged with. The rules of CAA have disappointed people, mostly undocumented, who have come from Bangladesh under circumstances where saving their lives meant more than arranging for documents for an unforeseen future where CAA was awaited.

“At a time we barely managed to make it to this side of the border, do you really think we would have been in a situation to bring our documents along with us? It was a harrowing journey just to reach safety on this side. We did not have birth certificates, it is hilarious that they are asking for birth certificates of my parents. I have nothing to show that I was born in Bangladesh or belonged to that country at some point. When I came to India, they had given some refugee card but that too got damaged during my stay at a camp. I only have this letter from my dead father which came from Bangladesh and on a Bangladeshi post card” said Thakur Mahanta, carefully holding the documents issued to him by the Indian authorities. He showed his Aadhaar card, PAN Card, passport issued by “Republic of India”, voter id card and also his ration card. “At BJP meetings we were told that once we get a citizenship card, it will be the number 1 proof of being an India, even after possessing all these Indian credentials”, he added expressing angst as how will he apply for CAA on the government portal without the requisite documents from Bangladesh.

CAA had been the poll promise of BJP in 2019, was even mentioned in their election manifesto. The promise to give citizenship had helped the saffron party woo the Matuas and Namasudras who had migrated from Bangladesh during the liberation war and for who citizenship had always been an emotive issue. Matuas are the second largest Scheduled Cast community in West Bengal with influence over 60 assembly constituencies. BJP in 2019 had managed to win five out of ten LokSabha seats in West Bengal reserved for the SC, riding high on the CAA sentiment. The Matuas who had welcomed CAA with jubilation and fanfare, have fallen into the depth of silence in less than three weeks since the rules were commissioned. While most of them have managed to procure Indian credentials including a voter id card over the period of time, but none of them have anything to show their link with Bangladesh.

Thus the story of helplessness not unique to Thakur Mahanta; it resonates deeply within every household of the Matua community in Bongaon. While initially embracing the Citizenship Amendment Act, they now find themselves lost in a maze of confusion regarding the necessary documentation. Being marginalized Hindus who fled to India during trying times, procuring any semblance of proof for their migration status proved to be a difficult task. The application process remains shrouded in ambiguity, leaving locals feeling confused. The Matuas stand at a critical juncture, grappling with the daunting challenge of attaining citizenship under the Citizenship Amendment Act amidst a stark scarcity of paperwork that proves their link to the countries they migrated from. “Will the government portal accept my father’s letter as a credible proof”, asked Mahanta with tears in his eyes, nonchalant to make any application for citizenship under CAA anymore.